Pregnancy is often described as a time of glow, yet for many women it brings congestion, inflammation and breakouts that seem to appear from nowhere. Acne that had long been under control can return with new persistence. The confusion begins when women search for advice and encounter lists of forbidden ingredients, contradictory guidance and little sense of what can actually be done. The truth is more measured. Acne in pregnancy has a clear biological explanation and, when understood properly, can be managed safely and effectively.

How does pregnancy change the skin?

Pregnancy reshapes every organ system and the skin reflects those internal shifts. Oestrogen, progesterone, human chorionic gonadotropin and androgens fluctuate across the trimesters while immune responses are recalibrated to protect the developing foetus. Sebaceous glands respond directly to these hormonal signals.

In early pregnancy, rising progesterone and relative androgen activity can increase sebum production. The oilier environment, combined with slower cell turnover inside hair follicles, favours the formation of microcomedones, the blocked pores that give rise to acne. At the same time, changes in the skin’s barrier and microbiome make the follicles more reactive. Many women notice new sensitivity, dryness or an altered pattern of oil production. Research shows small increases in transepidermal water loss and surface pH, alongside shifts in the balance of bacteria that live on the skin.

Some women improve after the first trimester as hormone levels stabilise, while others continue to experience acne throughout pregnancy or into the months after birth. The pattern is unpredictable but biologically logical.

Why doing nothing is not the safest option

Severe acne in pregnancy is not simply a cosmetic nuisance. It can be painful, interfere with sleep and leave permanent scarring or pigmentation. There is also an emotional cost that is well recognised in dermatology research. The absence of certain drugs does not mean the absence of treatment. The goal is to find an equilibrium between maternal and foetal safety while preserving skin integrity.

Treatments that are not used

A few medicines are firmly excluded because their risks are well documented.

Systemic and topical retinoids are the most familiar examples. Oral isotretinoin is a proven teratogen that can cause major developmental abnormalities. Topical retinoids such as tretinoin or adapalene are absorbed in only trace amounts but remain formally contraindicated because no ethical study could prove their safety.

Antibiotics from the tetracycline family, including doxycycline and minocycline, are avoided after the first trimester since they bind to calcium in developing teeth and bones. Spironolactone, often used for adult female acne, is also avoided because its anti-androgenic activity can interfere with normal male genital development. Other drugs occasionally used in dermatology, such as flutamide or high-dose salicylates, fall into the same category. These exclusions form the foundation of safe practice.

What treatments can be used?

Once those are set aside, the landscape opens again. Several topical and systemic options have reassuring safety profiles when used correctly.

Benzoyl peroxide has long been considered acceptable in all trimesters. It reduces the growth of Cutibacterium acnes, limits inflammation and helps prevent bacterial resistance when combined with antibiotics. The compound is absorbed only minimally through the skin and is broken down into benzoic acid, which the body clears quickly.

Azelaic acid is another cornerstone. It acts as a mild exfoliant and anti-inflammatory while helping to reduce the pigmentation that follows inflammation. Its systemic absorption is very low and studies have shown no evidence of foetal harm at therapeutic concentrations.

Topical antibiotics such as clindamycin or erythromycin can be used for inflammatory lesions, ideally together with benzoyl peroxide. They have long safety records in obstetric medicine and negligible systemic absorption when used on intact skin.

Gentle chemical exfoliants such as glycolic or lactic acid, or low-strength salicylic acid cleansers, can be helpful adjuncts. At cosmetic concentrations applied to small areas, they have not been associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.

A regimen built from these elements, non-alkaline cleanser, targeted topical therapy, non-comedogenic moisturiser and photoprotection, can control mild to moderate acne effectively without risk to the pregnancy.

Managing more severe disease

When acne is extensive or painful, more structured treatment may be justified. Certain oral antibiotics, including erythromycin base, azithromycin and cephalexin, are acceptable for short courses once past the first trimester. They are familiar to obstetricians and have been used safely for systemic infections for decades.

In very severe, inflammatory cases, short courses of oral corticosteroids can be considered after specialist discussion. This approach is used sparingly and only when scarring risk is high.

Procedural treatments are also relevant. Light-based therapies that use blue and red wavelengths can reduce bacterial load and calm inflammation without systemic drug exposure. Pulsed light and laser systems targeting superficial vascular and pigmentary changes can be used safely with correct parameters.

There is also a new generation of energy-based treatments that work without pharmaceuticals. AviClear, a 1726 nm laser, targets sebaceous glands selectively and can reduce oil production over time. Because it acts within the skin and involves no systemic medication, it offers a conceptually safer route for patients who are planning conception or cannot tolerate drugs. It would still be used cautiously during pregnancy itself, but it illustrates how device-based medicine is widening the options available to dermatologists.

The appeal and the risk of “natural”

Many women, wary of prescription drugs, turn to products labelled natural or clean. Unfortunately, these terms have no scientific meaning. Botanical extracts and essential oils can contain potent active compounds that have never been studied for reproductive safety. Tea tree oil, lavender and clove are frequent irritants; others, such as rosemary or bergamot oils, can provoke dermatitis. Natural does not mean non-systemic. Anything that crosses the skin barrier can enter the circulation, and without controlled data it is impossible to gauge risk. Evidence, not marketing language, should guide skincare decisions in pregnancy.

After delivery

Acne often lingers or reappears after birth. The sudden drop in oestrogen, stress and sleep deprivation all contribute. During breastfeeding, treatment choices expand slightly but still need caution.

Benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid and topical clindamycin remain suitable provided they are not applied to areas that come into contact with the infant’s mouth. Oral isotretinoin remains contraindicated and high-dose systemic agents are avoided. Tetracyclines may be used for brief courses if necessary, but not for long-term therapy. Once breastfeeding has ended, topical retinoids and other stronger actives can be reintroduced gradually, often as part of a plan to address residual scarring or pigmentation.

Why professional consultation is essential

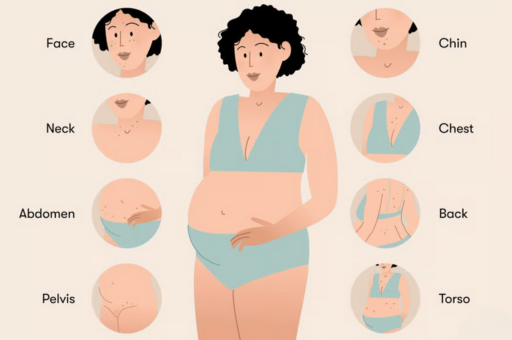

Acne in pregnancy overlaps dermatology, pharmacology and obstetrics. It cannot be reduced to a simple list of safe and unsafe ingredients. Severity, distribution, medical history and timing all influence what is reasonable.

A specialist will first confirm that the diagnosis is correct, as other conditions can mimic acne. They will then assess the pattern and depth of inflammation, review all medications and supplements, and consider the trimester of pregnancy. With these details, an individual plan can be created that controls inflammation, preserves the barrier and respects safety. You can contact our medical dermatology clinic on Harley Street to discuss your treatment.

A modern philosophy of care

Over the past decade, dermatology has moved away from absolute prohibition and towards informed choice. The objective is not to frighten women but to provide precise, evidence-based alternatives. Effective treatment during pregnancy relies on protecting the barrier, using agents with well-established safety data and introducing local energy-based therapies where appropriate.

At Self London, this approach forms the backbone of practice. Consultations begin with education, explaining clearly which drugs are off the table and which remain options. Treatment plans combine safe topical therapies such as azelaic acid or benzoyl peroxide with barrier-supportive skincare and, where appropriate, antibiotic or light-based intervention. For patients with high sebum output or significant scarring risk, doctor-led device treatments such as laser or ultrasound may be discussed once medically suitable.

The emphasis is long-term: to protect both mother and child while preventing avoidable scarring and loss of confidence.

The broader message

Pregnancy acne is a physiological response, not a personal failure. It reflects temporary hormonal and immune changes that can be managed when understood properly. The challenge is not the lack of options but the abundance of misinformation. A balanced plan, adapted to trimester and grounded in research, maintains skin health without compromising safety.

The best results come from science applied with restraint and intelligence. When the skin is treated as a living organ rather than a cosmetic surface, the outcome is not only clearer skin but a calmer, more confident experience of pregnancy itself.